- Home

- Jeff Stone

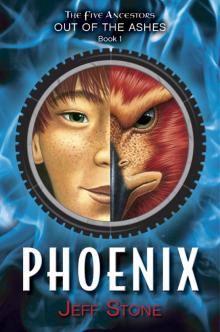

Phoenix Page 9

Phoenix Read online

Page 9

I dropped into a deep Horse Stance and thought quickly. I needed a kung fu form in which one person with a spear attacks another person who is empty-handed.

Say Sow Seh came to mind—“Four-Hand Snake.” This form was representative of snake-style kung fu, which happened to be my favorite and the one I did best. Timing and precision would be critical, because one false move by either individual with even a practice spear could mean serious injury, and I had the scars to prove it. Doing the form with an unknown partner who was holding a sharpened spear—a snake-head spear, no less—was practically suicidal. I hoped he knew this form as well as I did. There was only one way to find out.

“Say Sow Seh!” I challenged.

The old monk smiled and attacked, his foot-long spear tip heading straight for my liver. I weaved out of the way like an undulating serpent. As he pulled the spear back, he sliced at my thigh, attempting to sever my femoral artery, but I spun clear, keeping low to the ground.

The spear tip changed direction suddenly, and the old man thrust it at my back. I rolled forward, snaking around a tree as the razor-sharp blade barely missed me, cutting a wide swath of bark from an elm.

The old monk clearly knew the form, but he was playing for keeps. It made my blood boil. I emerged from behind the tree and spat like a cobra, raising my hands into snake-head fists.

The monk lifted the spear high over his head and began to spin it like a helicopter blade. Now it was my turn. I coiled and struck, lashing out at his abdomen with rigid fingers. I managed to hit my target before he could twist out of the way; however, I wished I hadn’t. His stomach was as hard as steel.

“Ow!” I said.

As I shook my tingling hands, he took a swing at my head with the spinning spear. I nearly forgot to duck.

I rolled backward and popped to my feet. The monk stopped swinging the spear. I readied myself for the next attack, which would be at my throat, when I heard a bloodcurdling scream from behind the old man.

My eyes widened as Hú Dié burst through the trees atop Trixie, pulling a high-speed wheelie. The old monk turned to see what was going on, and Hú Dié rammed him square in the chest with Trixie’s front tire. The monk went down awkwardly, the spear still in his hands.

Hú Dié released her grip on Trixie’s handlebars and unclipped her shoes, jumping off her bike. She landed on top of the huge old man, who was lying on his back.

“Hú Dié, NO!” I shouted.

She didn’t seem to hear. She clasped her hands together over her head and dropped to her knees, swinging her arms down toward the monk’s head as though she were swinging a sledgehammer.

The old man raised the thick spear shaft in front of his face to protect himself, but Hú Dié’s forearms smashed through the shaft as if it were a number-two pencil. The monk moved his head just in time to dodge the rest of Hú Dié’s brutal blow, which blasted an impressive crater in the dirt.

The old monk hissed like a dragon and shrugged Hú Dié off him. He sprang to his feet, and Hú Dié sprang to hers.

“Hú Dié!” I shouted again. “Stop! Everything is okay!”

Hú Dié shook her head as though clearing it of cobwebs. She turned to me. “Huh?”

I raised my arms in the universal gesture of surrender. “Everything is cool. He wasn’t attacking me for real. We were just doing a two-man kung fu form.”

Her eyes narrowed. “You know kung fu?”

“Yeah. I’m actually pretty good at it. Ask him.” I pointed toward the old monk.

The old man nodded. “Phoenix is quite good, and so are you, young lady. That trick with the bicycle was ingenious, and you shattered my favorite spear with your bare arms. Iron Forearm training, I presume?”

Hú Dié stared hard at the old monk. “None of your business. Who are you?”

The monk seemed taken aback by her disrespectful response. For a moment, I thought he was going to club her with one of the broken spear halves. But then his face softened, and he lowered his voice.

“Fair enough,” the old monk said. “Perhaps you do deserve some answers. You certainly have fought hard enough to earn them. Come, let me show you who I am.”

Hú Dié and I followed the old monk through the patch of new-growth forest. The old man carried the broken halves of his spear, while Hú Dié and I pushed our bikes. My helmet and pack hung from my handlebars, banging against Hú Dié’s dented helmet, which dangled from Trixie’s handlebars. Her helmet was even more beat up than before. I turned to her.

“Thank you for coming to my … um … rescue,” I said. “I appreciate it.”

Hú Dié took off her sunglasses and glared at me. “The next time you go on a ride with someone, you stick with that person at all times, understand?”

“I know. It’s just that …” My voice trailed off. I couldn’t decide whether to tell her why I’d wanted to leave her behind, or why I’d even come here in the first place. I felt as if she deserved to know after she had just risked her life for me.

“It’s just what?” she asked.

I hesitated. “I want to tell you something.”

“So tell me.”

I took a deep breath. “Have you ever heard of a substance called dragon bone?”

The old monk shot me a questioning look but said nothing.

Hú Dié looked from me to the monk, then back to me. She shook her head. “No. Is that why you came here?”

“Yes.”

“What is it?”

“A kind of medicine.”

“What does it do?”

“Basically, it helps people live longer—people like my grandfather. His remaining supply was stolen. If he doesn’t get more soon, he will die.”

The old monk stopped in his tracks. “Stolen?”

“Yes,” I said. “Two guys came to our house. They took all of it.”

“Who would do such a thing?” Hú Dié asked.

“I don’t know. I was thinking Grandfather might have been mixed up with Triad gangsters or a secret society or something long ago. One of the guys was Chinese.”

“Not the Triads,” the old monk said. “Your grandfather would have nothing to do with them.”

“Who could it be, then?”

“I do not know,” the old man replied.

Hú Dié looked at the monk. “Do you have more of this dragon bone?”

“Before we discuss this any further,” the old man said to Hú Dié, “I must insist that you tell me your name.”

“Fine,” she replied. “My name is Tiě Hú Dié. My father and I own a bicycle shop in Kaifeng.”

The old man stared at her for a moment. He nodded and seemed to look at her with new eyes. “Iron Butterfly. That explains your powerful arms. Though I’ve never spoken with him, I know of your father. I also knew of your grandfather, and of your great-grandfather. Your family is well known in certain circles. You sell more than bicycles, do you not?”

“Sometimes.”

The old man nodded. “To each his own. If your family knows how to do one thing, it is to keep secrets. I trust there is no harm in your hearing more of my conversation with Phoenix if you agree to never mention dragon bone to anyone.”

“Of course,” she said.

The old monk nodded again and turned to me. “You, either.”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

“Now that we have an understanding,” the old monk said, “Long is my name, not your grandfather’s.”

“Excuse me?” I said.

“Your grandfather’s real name is not Chénjí Long. It is Seh.”

I was confused. “Snake?”

“Correct. Shame on him for disguising his serpentine lineage. Shame on him, too, for denying you yours. You clearly move like a member of that species, and you do it well.”

“My grandfather is a good man,” I said in a defensive tone. “I owe everything to him.”

The old monk straightened. “I apologize if I have offended you. Your grandfather is indeed a very good man

in many respects. On the other hand, he is also a stubborn, secretive individual who would rather run from his past than embrace it. Your family history is long and dark, Phoenix. While it may be your grandfather’s nature to hide the truth from others, he should hide nothing from you. You are the last of his line. You are among the last of the Five Ancestors.”

I felt my head begin to spin.

“Hold on a minute,” Hú Dié said. “Are you saying that Phoenix is related to one of the Five Ancestors?”

The monk nodded. “He is, as am I. You both may call me Grandmaster Long. I am the last Dragon to come out of Cangzhen Temple.”

Hú Dié’s eyes widened. “So the legends are true? There really were five kids from this region who helped save China?”

“Yes.”

“When?”

“It was the Year of the Tiger, 1650,” Grandmaster Long said. “The children grew up right here.”

I was having a difficult time taking all of this in. What were Hú Dié and Grandmaster Long talking about? I asked, “Who were the Five Ancestors?”

“That is a very long story,” Grandmaster Long replied. “It will have to wait. First, we must address the dragon bone. How long has your grandfather been without it?”

I fought an overwhelming urge to push for more information and instead focused on Grandfather’s current situation. “Almost five days,” I said, “but he has an emergency supply of about a week’s worth.”

“You made it here quickly. I am impressed. I will do what I can for him. While he and I do not get along, I wish him no harm, and I value the fact that he sent you to me instead of infringing upon our mutual friend in Beijing. I am assuming PawPaw helped you find me.”

“Yes. We wouldn’t be here without her.”

Grandmaster Long looked up at the midafternoon sun. “Then let us make sure you do not disappoint those who have brought you this far. You have no chance of making it back to Kaifeng before dark. I suggest you spend the night here and leave at first light, for your grandfather’s sake. I will supply you with enough dragon bone to keep him in your life for as long as you and he wish. I like you, Phoenix. You have a good heart.”

I had a hard time believing my ears. This really was going to work out. I blinked away a tear that was beginning to form and bowed. “Thank you, Grandmaster Long. Thank you so much.”

“You are most welcome. Follow me to the temple and I shall show you what remains. Afterward, we will eat and I can tell you tales of Cangzhen Temple, if you would like.”

“Please do!” Hú Dié said enthusiastically.

“Ditto that,” I said.

Grandmaster Long smiled. “It pleases me to know that someone is interested in our history. I may as well begin the lesson right here, in this section of younger trees.” He raised his arms wide, a broken spear half in each hand. “This ground was devoid of anything except ankle-high grass for hundreds of years. Monks like myself took great pains to keep it that way because it allowed us to see invaders and attack them before they attacked us. Not too long ago, I decided to stop maintaining it. I am afraid I’m getting too old for that kind of work.”

He began to walk, leading us through the new-growth patch of forest for another seventy yards or so until we came to the remains of a stone wall that was at least seven feet tall. It was charred and crumbling, and entire sections were missing. Hú Dié and I leaned our bikes against the wall next to one of the larger gaps, which was wide enough for several people to walk through side by side.

I peered through the gap, taking in every detail. The wall had once surrounded a vast space filled with many one-story buildings of various sizes, all of which were made of stone and appeared to have been scorched by fire. Most of the buildings were crumbling, and nearly all had clay roof tiles that were cracked and broken. Cobblestone walks crisscrossed the ground, and some of the stones under the building eaves were splashed with black stains that I guessed had once been bloodred. This was no doubt the site of a horrific attack.

“Two hundred warrior monks died here,” Grandmaster Long said in a solemn tone. “Muskets and cannons were new to China at the time. The monks did not stand a chance.”

I looked at the damaged perimeter wall and couldn’t help thinking about pictures I’d seen of the famous Shaolin Temple nearby. While Shaolin was called a temple, it was actually a walled compound containing multiple temples and other buildings in which several hundred people could live in isolation, just like Cangzhen. The Shaolin compound had also been destroyed, but it was recently rebuilt. Millions of people from all over the world now visit it each year.

“Why don’t you rebuild Cangzhen like Shaolin has been?” I asked.

“I hope to,” Grandmaster Long said. “China is changing, and the time may soon be right to push Cangzhen Temple out of the ashes. However, making it a tourist destination is not exactly what I had in mind.”

“Yeah,” Hú Dié said. “ ‘Hidden Truth Temple’ doesn’t exactly sound like a vacation hot spot.”

I remembered asking Grandfather about the temple’s name and being told that I should ask here. I looked at Grandmaster Long. “What was hidden in this place?”

“Many things,” he replied. “And nothing.”

Hú Dié glanced suspiciously at Grandmaster Long.

“What is it?” he asked.

“My father says the same thing whenever he does not want me to know something.”

Grandmaster Long looked offended. “Do you not trust me?”

Hú Dié folded her arms. “You have done nothing to make me distrust you.”

“But I have done nothing to earn your trust, either, have I?”

Hú Dié didn’t respond.

“Fair enough,” Grandmaster Long said. “It is wise for a young woman to be cautious of strangers. I will show you something to prove my good intentions. Wait here. I will be right back.”

Grandmaster Long hurried deep into the compound, out of sight, and Hú Dié turned to me. “Do you trust this guy?”

“Why shouldn’t I?”

“Because you just met him.”

“I just met you, too.”

She cocked her arm to punch me, but I stepped backward, out of her reach. She lowered her fist.

“What about your grandfather?” she asked. “Does he trust this guy?”

“I guess so. He sent me here alone, didn’t he?”

She nodded. “I suppose you’re right. Maybe I have mixed feelings about him because I just fought with him.”

“Actually, it’s my fault that you attacked him. I went off on my own, remember? Riders are supposed to stick together.”

Hú Dié’s eyes narrowed. “Don’t remind me.”

Grandmaster Long returned carrying an ornate dragon-shaped vessel made of what looked like porcelain. I felt my pulse quicken. The container was a lot like the one Grandfather had used for his dragon bone, only much larger.

Grandmaster Long removed the vessel’s lid and showed the contents to me and Hú Dié. There was several times more dragon bone than Grandfather had had.

“Dragon bone, I presume?” Hú Dié asked.

“Yes,” Grandmaster Long replied. He looked at me. “I had planned to share this with you in the morning, but I will give you a portion for your grandfather now as an act of good faith and trust. I will find a suitable container and—” He stopped in midsentence, staring back the way we had come.

Hú Dié craned her neck, cocking her head to one side as if listening.

Then I heard it, too—the high-pitched whine of an off-road motorcycle, coming on fast. I looked down at the bits of fern frond still stuck to my legs. I had left a clear trail through the trees that anyone could follow. But who might be trailing us?

An instant later, I caught a glimpse of a motorcycle racing through the trees. It was traveling at an incredible speed. It reached the far edge of the new-growth section of elms, and I saw a second off-road motocross cycle coming up behind it. Both riders wore the reinforced ra

cing jackets and tinted, full face mask helmets favored by sport bike motorcyclists. Even so, I could tell by their physiques exactly who they were.

It was Slim and Meathead.

I pointed into the trees and shouted, “It’s the guys who stole my grandfather’s dragon bone!”

“Take cover!” Grandmaster Long said.

We raced through the large gap in the wall. Hú Dié and I ducked behind the wall, while Grandmaster Long cradled the large dragon bone vessel under one arm like a rugby ball and headed for a small, windowless building about the size of a backyard storage shed. The shed had no door, but its four stone walls appeared solid, and most of its roof was intact.

One of the motorcycle engines revved, and I peeked through a crack in the wall to see Slim take off ahead of Meathead. The thin man zipped through the young trees like a motocross champion, powering through the gap in the wall as Grandmaster Long slipped into the shed.

Slim gunned his engine and steered for the shed, and I saw him pull a fist-sized cylindrical object from his jacket and raise it toward his mouth. The object looked a lot like a mountain bike handlebar grip with a metal ring attached to one end. Slim pulled the ring out with his teeth, and as he raced past the shed, he threw the cylinder through the doorway.

BOOM!

A deafening blast erupted from within the stone shed, accompanied by a brilliant flash of light through the doorway that made me see stars. The object was some kind of flash-bang stun grenade.

I blinked several times and turned back to the gap, where I saw movement. It was Hú Dié. She’d gotten her mountain bike and was fiddling with Trixie’s quick-release seat post clamp. I took a step toward her but froze as Meathead reached the gap.

Hú Dié pulled the foot-long seat post out of Trixie’s frame, the narrow racing seat still attached to one end of the post. She gripped the end of the post opposite the seat and hurled the whole thing like a tomahawk at Meathead’s motorcycle. The rigid aluminum seat post caught in the heavy-duty spokes of the motorcycle’s front wheel, then jammed up against the back of the front fork.

Phoenix

Phoenix Jackal

Jackal Tiger

Tiger The Five Ancestors Book 7

The Five Ancestors Book 7 Lion

Lion Five Ancestors Out of the Ashes #1: Phoenix

Five Ancestors Out of the Ashes #1: Phoenix