- Home

- Jeff Stone

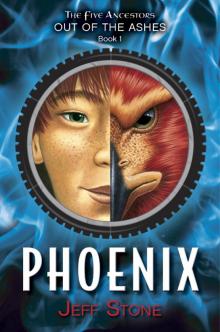

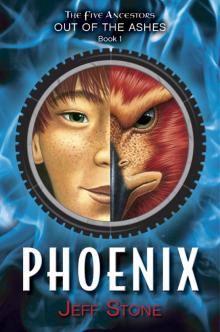

Five Ancestors Out of the Ashes #1: Phoenix

Five Ancestors Out of the Ashes #1: Phoenix Read online

The Five Ancestors

Book 1: Tiger

Book 2: Monkey

Book 3: Snake

Book 4: Crane

Book 5: Eagle

Book 6: Mouse

Book 7: Dragon

The Five Ancestors

OUT OF THE ASHES

Book 1: Phoenix

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2012 by Jeffrey S. Stone

Jacket art copyright © 2012 by Richard Cowdrey

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Random House and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Five Ancestors is a registered trademark of Jeffrey S. Stone

Visit us on the Web! randomhouse.com/kids

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stone, Jeff.

Phoenix / Jeff Stone. — 1st ed.

p. cm. — (Five ancestors: out of the ashes; bk. 1)

Summary: “When their home is robbed, thirteen-year-old Phoenix Collins, an up-and-coming amateur mountain-bike racer, discovers a shocking mystery about his grandfather, and Phoenix must travel to China and then to Texas to find some answers.” — Provided by publisher.

eISBN: 978-0-375-98759-5

[1. Bicycle motocross—Fiction. 2. Adventure and adventurers—Fiction. 3. Supernatural—Fiction. 4. Grandfathers—Fiction. 5. Orphans—Fiction. 6. China—Fiction. 7. Texas—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.S87783Pho 2012 [Fic]—dc23 2012006607

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

For Coach Bob Brooks.

Tag.

You’re it.

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Stage One - First Rule of Cycling: Never Blame the Bike

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Stage Two - Second Rule of Cycling: Change Gears Early and Often

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Stage Three - Final Rule of Cycling: To Finish First, You Must First Finish

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

About the Author

The pistol fired, and I hammered my feet down. My mountain bike shot forward like a bullet.

Elbows and knees flew in every direction as we raced, the other riders and I jockeying to be first onto the narrow dirt single-track. This was Town Run Trail Park, after all, not some perfectly groomed thirty-foot-wide BMX track. The route was a single lane over eight twisting miles of Indiana hardwoods and dried creek beds. It was nearly impossible to pass anyone in the tangle of low branches and exposed tree roots coming up, so commanding the lead at the beginning was crucial.

It took me less than fifteen seconds to shake the pack and hit the trailhead first. Disappearing into the trees, I leaned into the initial turn, feeling the wind through the vents in my battered helmet. Tree limbs bounced off my cracked goggles and duct-taped face mask, and thorny vines tore at my shin guards. My gloved knuckles smacked against massive tree trunks as my bike rocked from side to side on my push to increase my lead.

I attacked the single-track like an animal.

Like a wolf.

Like a cheetah.

Predator, not prey.

Back in the pack, you must outrun whatever is closest at your heels. Out front, it’s you against the trail. You have to attack it, or it will attack you.

Thirty seconds into the race, I was so far ahead that the others couldn’t even see my shadow. I whipped around a bend and saw the trail’s first climb. I shifted to the smallest sprocket on my rear wheel cassette and hit the dirt slope like a salmon swimming upstream.

My back tire began to fishtail violently, and I leaned out over the handlebars to get better balance and more traction. It was hard work. Most guys gave up at this point and simply jumped off their bike. They unclipped their feet from their quick-release pedals, shouldered their ride, and ran like a mountain goat. The trouble was, clipping back in at the top of the hill took time.

I didn’t have any time to lose, so I kept cranking. This was a race, after all. It didn’t matter that it was only a small-time event. Losing wasn’t an option.

I hate to lose.

I continued up the hill until I crested the rise; then I picked the cleanest line down the back side and hurled onward. As gravity sucked me down the rear slope, I stopped pedaling to conserve energy. I was going to need it. Ahead was the trail’s most dangerous section.

When I reached the end of the downhill run, I gently squeezed my index fingers over my brake levers, slowing. The trail had been dry so far, but the low ground looming before me harbored water overflowing from the White River mere yards away. Half an inch of turbid liquid floated atop several inches of muck. I flicked my right thumb, changing to an easier gear, and continued forward.

I motored into the rank sludge and immediately felt my hip flexor muscles begin to burn from the effort. The muck threatened to suck my tires right off the rims. Crud flew up in every direction as my rear wheel splattered a black line straight up my back, my front wheel slinging gelatinous clumps of earth up under my face mask and across the front of my goggles.

When I was halfway across the muck meadow, I heard a splash. I glanced over my shoulder, expecting to see a deer or maybe a raccoon.

It was neither. It was another rider.

I knew most of the dozen other racers, but I didn’t recognize this kid. He was a beast. His forearms were as thick as baseball bats, and the thighs bulging beneath his three-hundred-dollar skin suit looked as if they had been transplanted from an Olympic speed skater. I remembered seeing him at the starting line but had dismissed him as another aspiring muscle head wanting to race mountain bikes as a means of improving his cardio for other sports.

He was probably fifteen years old, the maximum age for this race bracket and two years older than I was. I’d assumed his expensive racing kit and full-suspension ultra-lightweight carbon bike had little to do with actual skill and more to do with rich parents.

But I was wrong. Whoever was behind that mirrored face mask could ride.

I shook my head. I’d never been very good at riding through water, and I needed to focus. I didn’t want to risk taking a dip in the bacteria soup surrounding me now. I decided to keep my pace slow and steady while the other kid pushed recklessly forward, water rooster-tailing off his bike like a wake behind a speedboat.

Unfortunately, his strategy worked better than mine. By the time my tires found firm ground, he was on top of me.

Literally.

The t

rail was slightly wider here, but it was littered with gnarled roots rising up out of the ground. This stretch was difficult to traverse solo, and potentially deadly if one rider tried to pass another.

The kid wanted to pass.

I wasn’t about to let him.

“Move it!” he snarled.

I held my ground.

He reached out and grabbed the back of my jersey, tugging violently. I had to hit my brakes to keep from getting pulled off my bike.

He let go and shot past me.

Crap. That wasn’t only illegal, it was incredibly dangerous. I flicked my thumb, changed gears, and began to hammer. My main strength is sprinting, and I caught him in seconds. The trail was still root-ridden, and it rattled my bones down to the marrow, but I didn’t care.

“On your left!” I shouted, knowing full well that he wouldn’t heed my request to pass on that side. He cut over to his left, and I made a move to pass him on the right.

He saw me coming and cut his wheel sharply back over to the right, slamming into me. I absorbed the impact instead of resisting it, like water flowing around a rock. I didn’t go down.

So the kid tried a different approach. He threw an elbow.

This blow caught me off guard. It struck me below the rib cage, nearly knocking the wind out of me. He cocked his arm for another swing, and I reacted without thinking. I stopped pedaling, twisted my left heel outward—freeing my shoe from its pedal clip—and kicked him in the thigh.

Hard.

He went down like a house imploding. He turtled into a ball and bounced over the rough ground, shouting a string of obscenities. Fortunately, there were no trees near enough for him to collide with, despite all the roots, and he and his bike eventually skidded to a halt.

Amazingly, in the blink of an eye he righted his bike and began to climb back on, still swearing. He appeared to be fine.

I put the hammer down once more. I pulled well ahead and reached the end of the roots, grateful that the nerve-numbing section was over. However, as soon as I was on smoother ground, I noticed that my bike didn’t feel right. The front wheel seemed spongy.

Bike parts rattled loose over those roots all the time, but this was different. My front wheel began to wobble, and I tickled my brake levers to reduce my speed. The last thing I wanted was for the front wheel to—

Crunch!

My bike stopped, but my body kept moving forward. I instinctively twisted my heels outward, my shoes ripping free of the pedals as I sailed over the handlebars. With my arms outstretched like Superman, I face-planted into the dirt. My worn chinstrap snapped, and my masked helmet bounced down the trail.

I sat up and spat. Wiping my sweaty brow, I quickly checked myself over. My chin was a little sore, but otherwise I was fine.

I looked back at my bike and frowned. The front wheel had tacoed, the rim folded almost completely in half. It took a special kind of problem for that to occur. I crawled over to my bike and checked the front spokes. Several were loose. I wiped a section of the rim clean and saw that a few of the spokes had come loose from the wheel when it folded in half, but others had fresh tool marks on the spoke nuts.

Someone had loosened them.

I heard the familiar hum of bike tires on dirt, and I glanced back up the trail to see the huge kid coming on like a locomotive. He shouted, “Get that rusted piece of junk off the trail!”

I hurried to my feet. Leaving a broken bike on the trail was dangerous for everyone, including me. That mountain of flesh might hit it and crash into me. I bent over, grabbing my bike with both hands, when the maniac roared like a lion, unclipped his foot, and unleashed a powerful kick at my face.

The reinforced toe of his mountain biking shoe caught me square on the jaw, and I blacked out.

I woke to a thick haze obscuring my vision. I was groggy, and everything I saw and heard came distorted and slow, as if my brain were floating in molasses. I felt fingers dance over my skull and across the back of my neck, and I realized I was lying flat on my back, my head cradled in my grandfather’s bony hands.

“Do not move,” Grandfather said. “Do not speak. Blink your eyes if you can understand me.”

I blinked.

“Very good, Phoenix,” Grandfather said. “Lie still while I examine you.”

I did as I was told. Grandfather wasn’t a doctor, but he knew more about healing than anyone I’d ever met, including my uncle Tí, who really was a doctor.

I tried to look around, but the only thing I could see was the vague outline of tree limbs dangling above me over the bike trail. It was early June, the first Saturday of summer vacation, and the foliage was thick. I doubted anyone had seen the cheap shot I took, which was fine with me.

Grandfather’s face came into view, and I watched him toss his long gray ponytail braid over his shoulder as he moved his black eyes to within an inch of my own. I could smell sweat on his cheeks. He must have run all the way here from the starting line. His sweat had a peculiar odor, which I attributed to the vast quantity of dried Chinese herbs he consumed. It wasn’t a bad smell, just sort of old and musty.

His gaze locked on mine, and I could tell he was checking my pupils for dilation and signs of concussion. He soon nodded, seemingly satisfied, then ran a yellowed fingernail over my bruised jaw. I flinched in pain, and he shook his head. I was not looking forward to explaining what had happened.

Punches and kicks, and the skills required to heal damage from them, were a big part of Grandfather’s life, which meant they were a big part of my life. He’d raised me ever since my parents died in a car wreck when I was a baby. He was some kind of kung fu master, though he wouldn’t admit it. I knew very little about him, in fact. To call him secretive would be an understatement, but he was very good to me.

I heard a bike approaching but couldn’t see who it was.

“Close your eyes,” Grandfather said.

I did so, grateful. The last thing I wanted now was a group conversation. It would be better to wait until I was alone with Grandfather before I shared the story of the race. He was going to be upset, and I didn’t want anyone else to hear the tongue-lashing I was bound to receive. They wouldn’t understand. None of them practiced kung fu.

When most people thought of kung fu, they envisioned bald Chinese guys in orange robes fighting with one another. While this is one element, there is so much more.

Kung fu actually means “accomplishment through effort,” and a person can apply its philosophies to anything, not just martial arts. They don’t even have to be Chinese to do it. I’m a good example. I’m only half-Chinese, but I try to live and breathe kung fu like the most hard-core monks living atop China’s tallest mountains do. I try to put one hundred percent of my effort into everything every day, whether it is martial arts, mountain biking, or homework. That’s what it means to be a kung fu practitioner.

I’ve been practicing kung fu ever since I could walk. Thanks to all that hard work, nobody could touch me on a mountain bike. Core strength exercises are the foundation of many martial arts, and they also happen to be the foundation for elite professional cyclists. Riding a bicycle involves far more than just your legs. If your torso and hips are powerful, it makes your legs exponentially stronger. Kung fu made me unstoppable on a bike.

Until now, that is.

Today I’d been beaten. It didn’t matter that I’d gotten kicked in the face or that someone had tampered with my bike. Cheaters were everywhere. As a student of kung fu, I needed to overcome any obstacle, especially if cheating was involved.

Grandfather exuded strength, which is why I felt like such a weakling for lying here now. As he rested my head on the ground and continued the injury probe, I couldn’t help but think about our similarities and differences. He was tall and thin, and he always stood ramrod straight. His hair was long, gray, and very thick, and he usually wore it pulled back in a heavy braid. He stood out in a crowd.

I stood out, too, but for different reasons. My mother had been from Chi

na, like Grandfather, while my straight-out-of-the-cornfields-of-Indiana father had been a redhead. The end result was that I have Asian facial features topped off with ratty brown hair that has a distinctly reddish tinge. I also have freckles and bright green eyes. I am of average height, and to see me walking down the street, you probably wouldn’t guess that I’m an athlete, unlike the heavily muscled kid who kicked me. While muscular people can dominate in certain sports, that physique generally doesn’t translate into a podium finish in cycling, because riding a bike most often comes down to power-to-weight ratio. When people think of cyclists, they don’t think Arnold Schwarzenegger. They think Lance Armstrong.

I’m built like a bird, strong and light as a feather. It is Chinese tradition that a woman’s father names her son, and Grandfather couldn’t have picked a better name for me—Phoenix. Grandfather was amazing in so many ways. He’d given up his life in China to move to Indiana and take care of me. I couldn’t even take care of my bike.

What had gone wrong?

I went through a mental checklist. I’d given my bike a complete physical two nights ago and hadn’t ridden it since. I hadn’t left my bike unattended here at the trail park. No one else besides Grandfather had even touched my bike in the last forty-eight hours.

Unless …

It was a stretch, but there had been two guys in our backyard when I’d come home from school yesterday. Two men in white disposable jumpsuits were taking soil samples from the septic field in our yard, the area where the wastewater tank for our house was buried. A van in the driveway had EPA—ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY stenciled on the sides.

The men were such an odd pair that I watched them as they packed up and hurried off. One guy seemed average in every way except for the way he moved. He had the precise movements of a martial artist. Grandfather moved like that.

As for the other guy, he would have put the kid who kicked me to shame in the muscle department. He was a freak. I remembered thinking that he should have been inspected by the EPA, not working for them. It looked as if he’d been pumped with so many chemicals, he probably glowed in the dark. I even made up nicknames for these guys: Slim and Meathead.

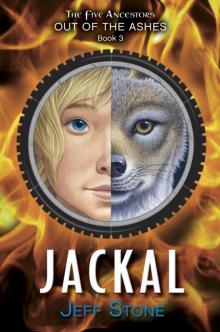

Phoenix

Phoenix Jackal

Jackal Tiger

Tiger The Five Ancestors Book 7

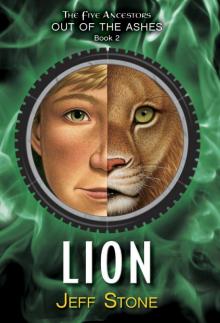

The Five Ancestors Book 7 Lion

Lion Five Ancestors Out of the Ashes #1: Phoenix

Five Ancestors Out of the Ashes #1: Phoenix